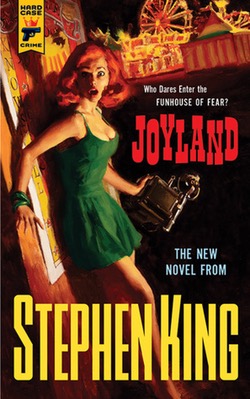

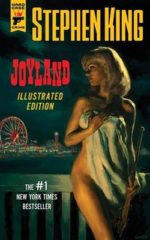

Around 2012, Stephen King had an idea for a book. It was a small book, grafting an image he’d had 20 years ago (a kid in a wheelchair on a beach flying a kite) to his urge to write about carnivals. Set in 1973, it was kind of a mystery, but mostly a coming-of-age story about a college kid “finding his feet after a heartbreak.” It wasn’t the kind of book his publisher, Simon & Schuster, wanted. They liked big fat books, like Doctor Sleep, King’s sequel to The Shining coming out later in 2013. So King returned to the scene of the (Hard Case) Crime and published it with the folks who’d previously handled his other slim, not-really-a-horror-or-a-mystery novel, The Colorado Kid. Also returning was Glen Orbik handling cover duties, best known for reproducing the lush, fully-painted style of pulp paperbacks for everything from movie posters, to comic books, to the California Bar Association.

Hard Case Crime specializes in publishing books that aren’t what they appear. Everything they release, from Stephen King to Max Allan Collins, gets a painted cover that makes it look like old school, disreputable pulp no matter what the contents. That made it a good fit for both The Colorado Kid and Joyland, since neither is what it appears, either. The Colorado Kid barely even had a story and was, instead, a philosophical logic problem that doubled as a rumination on the failures of storytelling and the power of mysteries. Joyland looks like a thriller and even reads a bit like a thriller with its haunted funhouses, carny talk, psychic children, and serial killers, but it’s mostly about an emo college kid getting dumped.

Maine native, Devin Jones, is working his way through the University of New Hampshire. Cleaning trays in the cafeteria, he spots an ad in a discarded Carolina Living magazine, “Work Close to Heaven!” It’s for Joyland Amusement Park down on the North Carolina coast, and he signs up, goes down, rents a room in a boarding house, and finds a bunch of new friends: not only Tom and Erin, who are newbies like himself, but also Lane Hardy and Madame Fortuna, who are longtime carnies. He also meets the ghost of Linda Gray who haunts the Horror House ride where, years ago, her boyfriend took her on a date, waited till the ride was dark, then slit her throat, and tossed her over the side. Decades later, Linda’s killer remains at large and it’s Tom, not Devin, who sees her ghost when the bored friends go looking for her on their day off. Not only does Devin vow to solve the mystery of who murdered Linda Gray, he also saves a little girl from choking to death while dressed in a big fur suit as Joyland’s mascot, Howie the Happy Hound, and he befriends Mike Ross, a psychic but terminally ill kid in a wheelchair he spots every day as he walks up the beach to work. He also meets Mike’s bitter mom, Annie. And none of these machine gun character introductions or frantic plotting has a thing to do with what the book’s actually about.

Maine native, Devin Jones, is working his way through the University of New Hampshire. Cleaning trays in the cafeteria, he spots an ad in a discarded Carolina Living magazine, “Work Close to Heaven!” It’s for Joyland Amusement Park down on the North Carolina coast, and he signs up, goes down, rents a room in a boarding house, and finds a bunch of new friends: not only Tom and Erin, who are newbies like himself, but also Lane Hardy and Madame Fortuna, who are longtime carnies. He also meets the ghost of Linda Gray who haunts the Horror House ride where, years ago, her boyfriend took her on a date, waited till the ride was dark, then slit her throat, and tossed her over the side. Decades later, Linda’s killer remains at large and it’s Tom, not Devin, who sees her ghost when the bored friends go looking for her on their day off. Not only does Devin vow to solve the mystery of who murdered Linda Gray, he also saves a little girl from choking to death while dressed in a big fur suit as Joyland’s mascot, Howie the Happy Hound, and he befriends Mike Ross, a psychic but terminally ill kid in a wheelchair he spots every day as he walks up the beach to work. He also meets Mike’s bitter mom, Annie. And none of these machine gun character introductions or frantic plotting has a thing to do with what the book’s actually about.

King says that for him the heart of the book is stated quite clearly when Joyland’s owner, 93-year-old Bradley Easterbrook, gives a speech to his new employees, telling them, “We don’t sell furniture. We don’t sell cars. We don’t sell land or houses or retirement funds. We have no political agenda. We sell fun. Never forget that.” That’s a heck of a mission statement and one King does his best to live up to, tap dancing as fast as he can to make this book as fun as possible. He peppers Joyland with made-up carny talk like “donniker” (bathroom), “point” (good-looking girl), and “spree” (park attraction) that he gleefully admits to fabricating out of whole cloth. Every single carny is a carefully designed caricature, from the hunky loner with the soul of a poet to the Earth mother fortune teller with the New York accent and the Eastern European shtick. A big part of the reason King tries so hard to make it such a fast and breezy trip to the fun park is to counterbalance the heavy heart of the book that occasionally threatens to weigh it down.

Stephen King has been married to Tabitha King (née Tabitha Jane Spruce) almost all his life. They met at the University of Maine in 1969 when he was 22 and she was 20 and got married two years later. Also a published author, she’s been King’s first reader since the beginning and plays a major part in his life and his work. But before there was Tabitha King, there was another woman in King’s life, a girlfriend of four years who dumped him his sophomore year in college. At that time he was writing a novel about a race riot at a high school called A Sword in the Darkness and, as he said in a 1984 interview:

Stephen King has been married to Tabitha King (née Tabitha Jane Spruce) almost all his life. They met at the University of Maine in 1969 when he was 22 and she was 20 and got married two years later. Also a published author, she’s been King’s first reader since the beginning and plays a major part in his life and his work. But before there was Tabitha King, there was another woman in King’s life, a girlfriend of four years who dumped him his sophomore year in college. At that time he was writing a novel about a race riot at a high school called A Sword in the Darkness and, as he said in a 1984 interview:

“I had lost my girlfriend of four years and this book seemed to be constantly, ceaselessly pawing over that relationship and trying to make some sense of it. And that doesn’t make for good fiction.”

Now, he returns to the scene of the crime in Joyland, which starts when Devin Jones hears the worst sentence in the world, spoken by his longterm girlfriend, Wendy Keegan, when they realize that his summer job at Joyland means they’ll spend the summer separated by a couple of hundred miles: “I’ll miss you like mad, but really, Dev, we could probably use some time apart.” You can practically hear his heart break, and even narrating the book from the perspective of an adult in late middle-age, the break-up still seems unnecessarily cruel to Devin. As he says, “I’m in my sixties now, my hair is gray and I’m a prostate cancer survivor, but I still want to know why I wasn’t good enough for Wendy Keegan.” It’s a mopey mission statement for a book powered by the idea that “We sell fun.” King shovels on the high drama and the breast-beating, delivering all the romance, passion, explosive melancholy of being utterly miserable and heartbroken and young. The only thing better than the feel of first love is that first fabulous break-up, and Devin wallows gloriously. He listens to Pink Floyd albums over and over again while sitting in his dark bedroom staring out over the nighttime sea. Sometimes he plays The Doors. “Such a really bad case of the twenty-ones,” he moans. “I know, I know.”

But the flip side of the lows are the highs, and Joyland exults in melodrama, whether it’s a dying child in a wheelchair who can predict the future, a hostage situation on top of a Ferris Wheel during a lightning storm, lit by operatic flashes of lightning, or a restless ghost silently begging for justice, this is the stuff of high gothic, which King plays as straight as possible. A serial killer stalks Joyland! Devin has sex with an older woman that cures him of his heartbreak! Every moment of this book is played at maximum volume, every dramatic incident is painted in the bright red and gold of a merry-go-round, every emotion is lathered into melodrama. Light and breezy, with more incident packed into its slim 288 pages than most of his books, this is Carnival King, keeping all his balls in the air and making it up as he goes along (he says that he didn’t even know who his killer was until he got near the end of the book). But even King at his lightest and most charming can barely balance the darker weight that’s been tugging at his latest books.

But the flip side of the lows are the highs, and Joyland exults in melodrama, whether it’s a dying child in a wheelchair who can predict the future, a hostage situation on top of a Ferris Wheel during a lightning storm, lit by operatic flashes of lightning, or a restless ghost silently begging for justice, this is the stuff of high gothic, which King plays as straight as possible. A serial killer stalks Joyland! Devin has sex with an older woman that cures him of his heartbreak! Every moment of this book is played at maximum volume, every dramatic incident is painted in the bright red and gold of a merry-go-round, every emotion is lathered into melodrama. Light and breezy, with more incident packed into its slim 288 pages than most of his books, this is Carnival King, keeping all his balls in the air and making it up as he goes along (he says that he didn’t even know who his killer was until he got near the end of the book). But even King at his lightest and most charming can barely balance the darker weight that’s been tugging at his latest books.

More and more characters in King are dying of cancer, with two people passing away from it in 11/22/63 and now in Joyland you have a narrator who’s a cancer survivor, and his mother who’s dead of breast cancer when the book begins. On top of that you have the genuine pain of Devin’s heartbreak. As silly as his wallowing becomes, his pain is acute and occasionally hard to write off. Every first love leaves a damaged, bomb-blasted victim behind. That’s just a universal truth we don’t like to think about. Loss is a part of growing up, and as characters die and the fun park shuts down for the season Joyland acquires a kind of autumnal melancholy that feels like late career Ray Bradbury more than anything. “The last good time always comes,” Dev says. “And when you see the darkness creeping toward you, you hold on to what was bright and good. You hold on for dear life.”

Joyland, like 11/22/63, is an old man’s book, and at its heart is the knowledge that every fun park eventually closes for the season, and everyone you love will eventually go away. Despite that bummer, it did well. Coming out only in paperback, it spent seven weeks at number one on the New York Times Paperback Bestseller List, then a further five weeks in the top ten, finally disappearing from the top 20 after 18 weeks. King wanted it to be released in paperback only, like the books in the drugstore spinner racks of his childhood, but eleven months later on April 8, 2014 he succumbed to pressure and allowed an audiobook to be released, and then a hardcover almost a year later on September 23, 2015.

Joyland, like 11/22/63, is an old man’s book, and at its heart is the knowledge that every fun park eventually closes for the season, and everyone you love will eventually go away. Despite that bummer, it did well. Coming out only in paperback, it spent seven weeks at number one on the New York Times Paperback Bestseller List, then a further five weeks in the top ten, finally disappearing from the top 20 after 18 weeks. King wanted it to be released in paperback only, like the books in the drugstore spinner racks of his childhood, but eleven months later on April 8, 2014 he succumbed to pressure and allowed an audiobook to be released, and then a hardcover almost a year later on September 23, 2015.

Joyland is a slight, fun book with a touch of winter’s chill around the edges, and the nice thing about King is that he’s earned his right to these smaller books. By now, we trust in his work ethic. We’ve come to know, and believe in, his rhythms. We know there will be another book after this, and another after that. It’s not about the money anymore, and it hasn’t been for a long time. As long as he’s able, King will keep telling stories, and if we don’t like this one, or if that one’s too slight, or if this one over here doesn’t fit the mood we’re in, there will always be another. And another, and another, and another. Until one day, as Joyland reminds us, there won’t be.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He is the author of Horrorstör, the only novel about a haunted Scandinavian furniture store you’ll ever need, and My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist. His next book is a non-fiction chronicle of the boom in horror paperback publishing in the Seventies and Eighties that followed in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. It’s called Paperbacks from Hell and will hit shelves in September 19th.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He is the author of Horrorstör, the only novel about a haunted Scandinavian furniture store you’ll ever need, and My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist. His next book is a non-fiction chronicle of the boom in horror paperback publishing in the Seventies and Eighties that followed in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and Thomas Tryon’s The Other. It’s called Paperbacks from Hell and will hit shelves in September 19th.